By Keep It Local, Florida

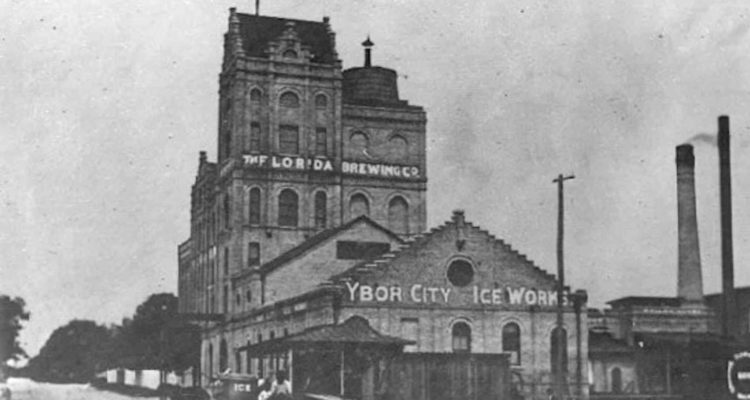

Ybor City, 1897 – Celebrated cigar industrialists Vicente Ybor and Eduardo Manrara found The Florida Brewing Company—the Sunshine State’s first brewery. A year later, they’re serving beer to 30,000 troops on deployment in the Spanish-American War. According to local legend, Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders paid a visit while passing through. The brewery managed to thrive under the radar during Prohibition and survived until the 1960s when it, along with the rest of Florida’s breweries, vanished—not to return … until now.

Craft breweries have reemerged in local communities throughout Florida as sources of economic and cultural vitalization. But why did they disappear in the first place? And why the sudden renaissance?

Several post-prohibition laws inadvertently favored large beer conglomerates. Eventually, small breweries were forced to close, or otherwise sell themselves to national breweries—ushering in an age of homogenous, mass produced beer.

While Florida wasn’t ground zero for the Craft Beer Boom, it’s now one of the biggest states for local craft beer growth.

From a legislative standpoint, what changed to make Florida’s Beer Boom possible? Not much, according to Luch Scremin, owner of Jacksonville’s Engine 15 Brewing Co. “I can say that legislatively, state law hasn’t been much help,” he said. “There’s no significant difference between now and 10 years ago.”

“The bottle law change helped a little,” offered Michael N. Bryant, owner of the Dunedin Brewery, referencing the legislature’s repeal of a previous ban on 22-ounce bottles. But with the three tier system still in place: “there’s still a cap on everybody in this state,” says Bryant.

The three tier system refers to the production, distribution and sale of alcohol. It was a post-Prohibition law created to ensure no single entity had a monopoly on all three tiers. However well-intentioned, the law gave wholesalers “all the power and all the money,” said Scremin.

Both brewers pointed to local governments’ willingness to change zoning laws and rethink regulation, making it easier for brewers to open production. “There’s been a lot more awareness,” said Scremin.

Kevin Crowder of Redevelopment Management Associates is currently working with the North Miami Beach Community Redevelopment Agency to create a brewery district within the city. He says local governments see value in the pioneering spirit of microbreweries. “They open in neighborhoods other businesses won’t and bring a level of credibility,” explained Crowder.

Scremin noticed the same thing when his brewery expanded to downtown Jacksonville. “Most people thought we were crazy,” he said. “Now we have an event venue here. The Jacksonville Cultural Council event was here. A non-profit just moved down the street. There’s more interest in the area now.”

As with any local business, microbreweries mean new jobs and more tax revenue, but Greg Rice, Planning and Development Director for the City of Dunedin, says microbreweries also serve as tourist attractions. “It was Michael Bryant’s idea to help others start their own breweries in Dunedin,” he said. “Instead of creating competition for himself, he actually helped turn Dunedin into a craft beer destination.”

Most craft breweries draw a different crowd than your average bar or club. “Typically, craft beer drinkers are interested in quality, not quantity,” says Scremin. “Our beers aren’t brewed for pure intoxication.”

Many craft breweries try to foster family-friendly environments. In fact, Engine 15 Brewing’s beer garden in downtown Jacksonville features a playground equipped with a giant pirate ship, which Scremin built himself.

“Lots of regulation was written from the perspective that alcohol establishments are a nuisance,” said Crowder. “If you want to attract breweries to your area, you can’t treat breweries like you would a bar or club.”

Or a production brewery, noted Scremin: “10 years ago [local governments] would’ve lumped us in with large production breweries, but they’ve since undergone an education about what craft breweries are.”

According to Greg Rice, that was the catalyst for Dunedin’s craft beer boom. “We adjusted our downtown core’s zoning, because while microbreweries produce beer, they’re not the loud manufacturing plants that large production breweries are,” said Rice. “So we changed our code to include microbreweries as Permitted Use. Now there’s no public hearings. No approvals beyond the staff level.”

According to Kevin Crowder, local governments can also take care of some of the due diligence microbreweries would ordinarily have to take care of themselves. “Market analysis, identifying available real estate, any zoning changes. You can cut down decision time for the brewers if you have all that ready,” said Crowder.

Bryant and Scremin agreed: make zoning easier to change and talk to brewers so you understand their business.

“Take a really good look at your zoning and preemptively find hurdles microbreweries will encounter,” says Scremin.

Today, the building that housed Florida’s first brewery still stands as the tallest in Ybor City. It’s since been restored and converted into law offices. The aromas of rich malt and bitter hops that once wafted through its open floors are long gone by now—but the tallest building in Ybor remains a monument to the pioneering spirit of craft brew.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.